The Case for Etc.

Why this tiny word deserves our attention.

What if the most overlooked word in Tanya is not a casual ellipsis, but a doorway to infinity?

Baruch Hashem, we live in extraordinary times. The Tanya—the foundational text of the Chabad movement—has reached every corner of the world. Translations abound, commentaries proliferate, classes echo in every language of humankind. Today, even in the remotest corner of the globe, one can open Tanya and feel the Alter Rebbe speaking directly to our soul.

But with great privilege comes great responsibility. If we are to properly transmit the message of the Alter Rebbe, we must treat every word of the Tanya not merely as words but as treasures. Every abbreviation is measured and every nuance contains an ocean of knowledge.

We see this clearly stated in Sefer HaYom Yom1 where it records how the Alter Rebbe spent 20 years “choosing every single word precisely.” The Frediker Rebbe2 relates that once, the Alter Rebbe sat so deeply engrossed in deciding whether to include a single “vav” in a spot in Tanya that he didn’t notice his own older brother patiently waiting beside him for an hour3. If such was the gravity of a single letter, how much more so an entire word!

And yet, there is one word, threaded consistently throughout the Alter Rebbe’s holy text, which may appear to the casual eye as a mere filler — the word “etc.” — “וגו’” or “וכו’.

But the Alter Rebbe does not write casually. His every word is a lantern. His every literary decision a map. Which means that every “etc.” is not merely an ellipsis, but an invitation to the astute reader, “Here lies a deeper connection; here I point you toward another sugya, another chapter, another dimension.” If we distranslate or gloss over any one of these “etc”, we withhold from our students a component which the Alter Rebbe precisely placed there and which he considered vital to the message at hand. Who are we to know how many hours of the Alter Rebbe’s valuable he spent deliberating over each and every one of these “etc.”?

So, at the very least, when we study Tanya or translate it for others, we must be vigilant to translate every word of the Alter Rebbe, including each and every “etc.”

Proof from the Rebbe:

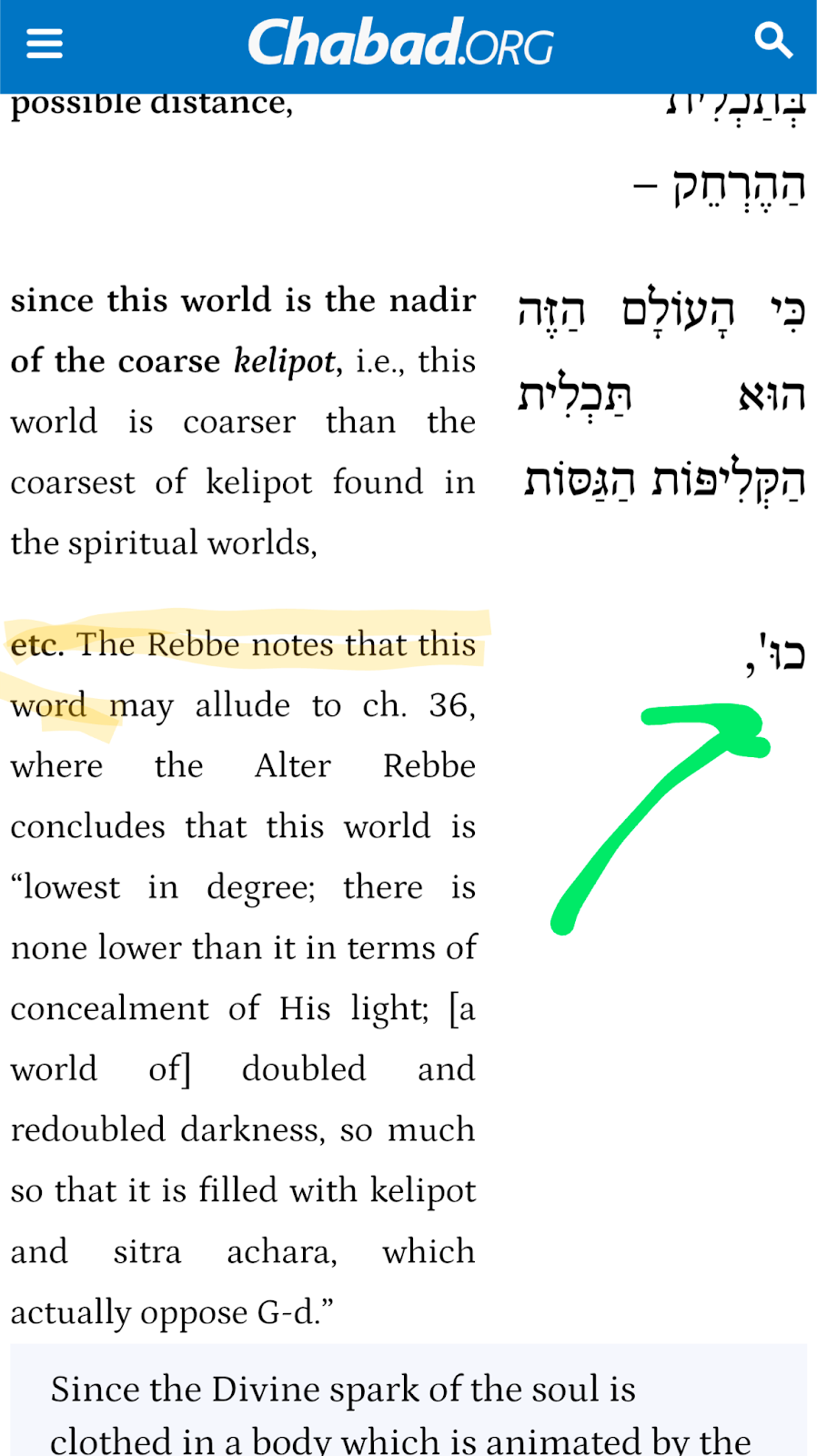

In Chapter 45 of the Tanya, the Alter Rebbe writes:

“..this world is coarser than the coarsest of kelipot found in the spiritual worlds, etc.”

The Rebbe explains that the “etc” here directs us to Chapter 36, where the Alter Rebbe expounds upon what it means that “there is none lower” than this world. We see clearly how the Rebbe himself is showing us that without this one little “etc” the bridge between the chapters is lost and the message of the Alter Rebbe incomplete.

Proof from the Alter Rebbe:

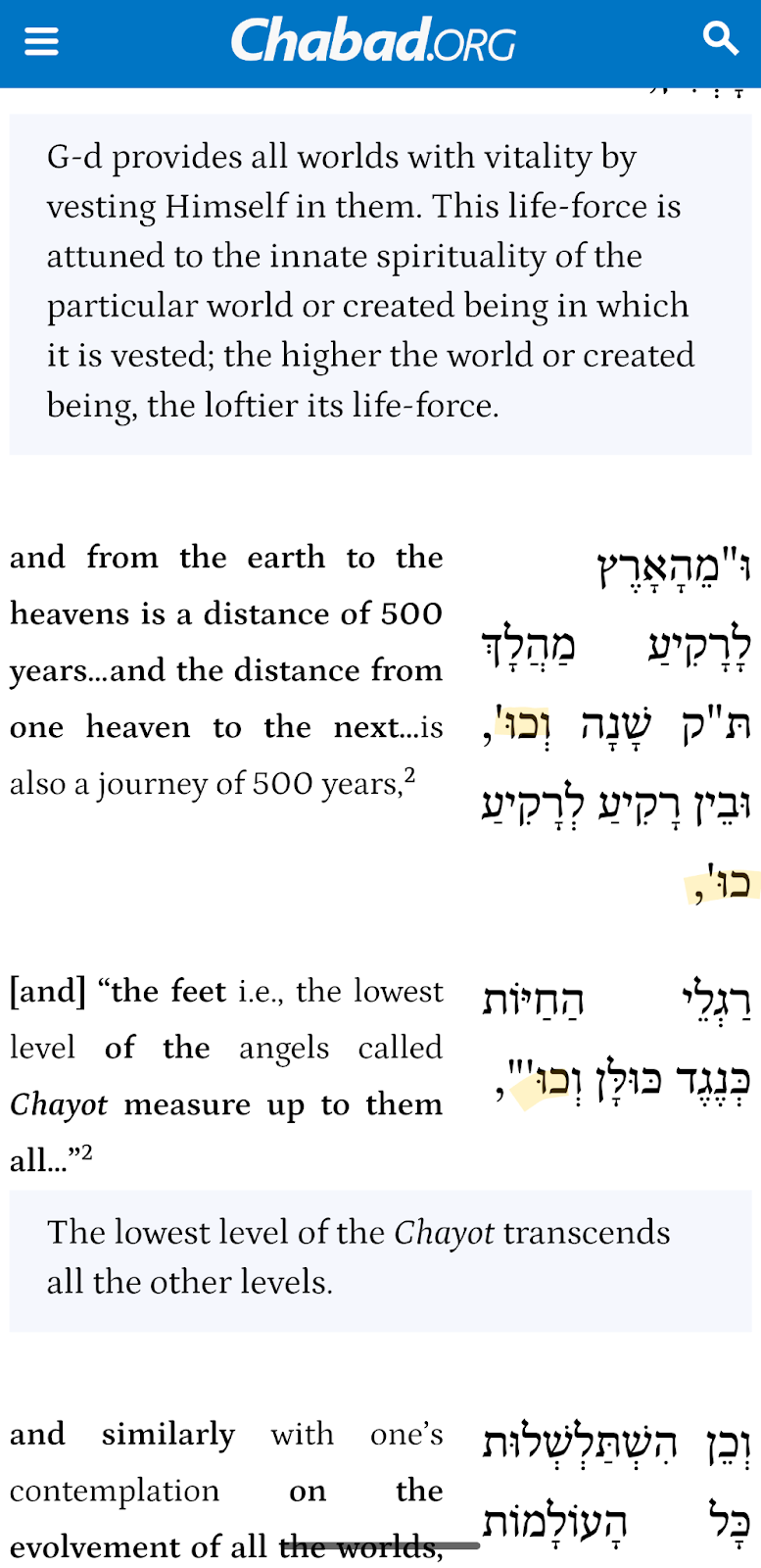

In Chapter 43, the Alter Rebbe writes:

“...and from the earth to the heavens is a distance of 500 years and etc and the distance from one heaven to the next, etc [and] “the feet i.e., the lowest level of the angels called Chayot measure up to them all and etc.”

In the original Hebrew, the words “and etc” appear as “וכו” and the word “etc” as “ כו” (without the Vav). In other words, within a single line, he alternates between the two. Why? I don’t know. But to dismiss the specificity of this nuance is to dismiss the deliberation of the author himself.

Proof from Chabad translators:

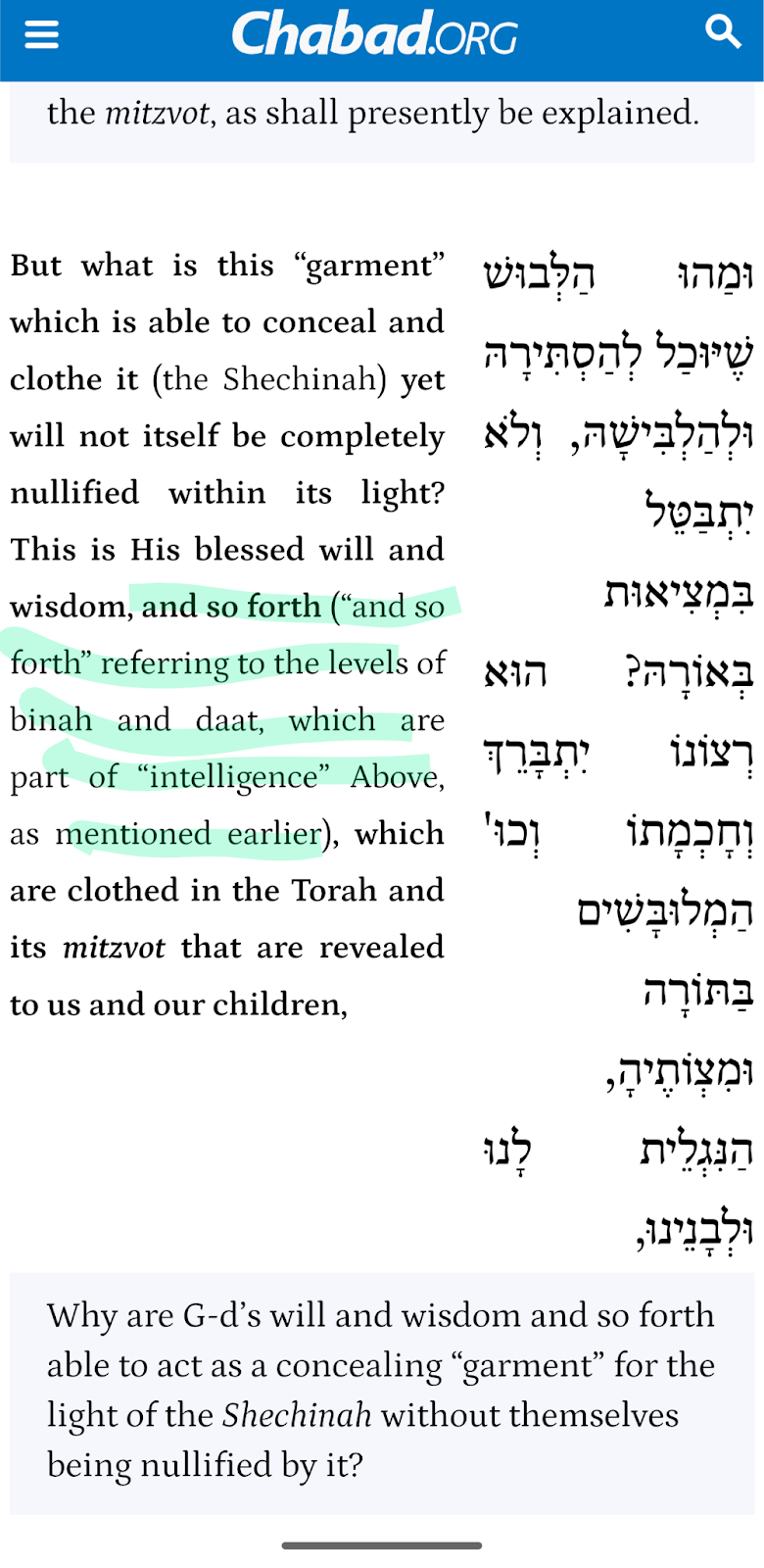

Teachers of Tanya have a sacred role in transmitting the Alter Rebbe’s message with complete fidelity. Ergo, we must translate every word, abbreviation, and every “etc.” exactly as the Alter Rebbe intended. This way, teacher and student alike can study the original text alongside any commentary, without conflating the two.

So when the translator of Chabad.org’s Chapter 52 faithfully renders “וכו’” as “and so forth,” and only then offers parenthetical explanation, they fulfill this principle: transmit the Alter Rebbe’s words exactly, let clarification come only afterwards.

Why This Matters

The Rebbe taught us that every Jew is a letter in the Sefer Torah. If even one letter is missing, the Torah is invalid. If this is true of the Written Torah, how much more so of the “Written Torah of Chassidus”4, the Tanya.

So let us commit to the following: When we learn and teach Tanya—let every “etc.” be translated in its proper place. This way, we transmit the Tanya exactly as the Alter Rebbe intended; whole and shining, to every person, in every language, in every land.

Even if we don’t understand why the Alter Rebbe put an “etc” in a particular spot, soon we will behold the revelation of Moshiach Tzidkeinu, when the hidden meaning of every “etc.” will be explained and we will see with our own eyes how every word, every letter, and every person matters in ways unfathomable to mere mortal minds.

Indeed, we know from Tanya that redemption often begins not with grand gestures, but with holding sacred the smallest detail, smallest person, and smallest choice.

Further Reading & Sources:

My Mashpia in Yeshivah, Rabbi Mendel Shapiro, taught me, “The greatest way to be a Chossid of the Rebbe is to learn how the Rebbe was a Chossid of his Rebbe.” In other words, when we model our own behavior and way of life after the Rebbe, it enhances our “hiskashrus” and connection to the Rebbe.

In this vein, here are some more examples highlighting how the Rebbe taught us that how precise every “etc” is not just in Tanya but in Rashi’s commentary and across all others areas of Torah scholarship.

Lekutei Sichos, vol. 9, pp. 33–48.

Torat Menachem 5727, Shabbat Parshat Vayechi, 11 Tevet, vol. 48, pp. 406–7.

Abraham Grossman, Rashi (Littman), pp. 78–79.

Eric Lawee, Rashi’s Commentary on the Torah, p. 24.

Hayom Yom, entry for 6 Adar II

See the letter of the Rebbe Rayatz appearing in Sefer Kitzurim VeHe’aros LeTanya, p. 118ff., in Likkutei Sichos, Vol. 4, p. 1212, footnote 3, and in Reshimas HaYoman (Kehot, N.Y., 5766/2006), p. 236; Lessons In Tanya, Vol. 2, p. 610.

The Alter Rebbe added: “It’s worth giving away six weeks for a letter vav in the Book for Beinonim [i.e., Tanya], so that the seventh week will be lit up with an intense illumination.”

See the letters of the previous Lubavitcher Rebbe, Vol IV, 261.